I’m a bit behind the times! Substack is all the rage now, I gather, and I haven’t even posted on this blog for nearly two years, despite payment for the domain name having automatically renewed. I’ve decided to keep the blog going for the time being to share the stories of my family’s Great War service. What follows is an edited version of a write up in my ongoing family history project.

I’m starting with a rogue of the family! Allen Wright’s is a tale of multiple absences without leave whilst home based, being gassed and wounded whilst overseas, other illnesses to add to the mix, and an unfortunate accident following demobilisation.

Astonishingly, the service file of Allen Wright survived the blitz bombing (unlike others in my family), even more astonishingly it contains 85 images! Having trawled through it (of course it is not in date order) I found many duplicate documents, some completely blank forms and some printed guidance forms for administrators of one sort or another. Even so Allen kept the army busy. He may not have been born within the sound of Bow Bells, but I get the impression he was probably that archetypal cheeky cockney.

Going back in the mists of time I have ancestors who hailed from Ireland, Scotland, the north-east and the midlands, but by the mid-19th Century the various strands were established in south-east London – or rather Southwark, Surrey as the area was then. Southwark may have been somewhat leafy when the first of my ancestors arrived early in the century, but by the end of the century the semi-rural character of the area had completely changed by creeping industrialisation and the replacement by docks of the many wharves on the River Thames. Crowded tenement buildings housed the families of workers, including those of the Bermondsey leather trade in a network of streets full of outdoor tanning pits where Allen spent his childhood.

When Allen Wright was born circa 1890 his father, John, was a tanner. Prior and subsequent censuses described his mother, Ellen, as a machinist. I find this quite amazing as Allen was the youngest of the seven children who survived, but Ellen actually gave birth to fourteen babies, as per the 1911 census. This census also tells us that John was now a greengrocer working on his own account and that Allen was working with him. When Allen married on 23rd November 1913 the marriage certificate also described John as a greengrocer, but Allen was a general labourer. At the time of their marriage Allen and Mary Ann lived at different numbers of Crossfield Street, which is now Deptford, London, SE8. Subsequently, they moved into another building, number 26, on the same street.

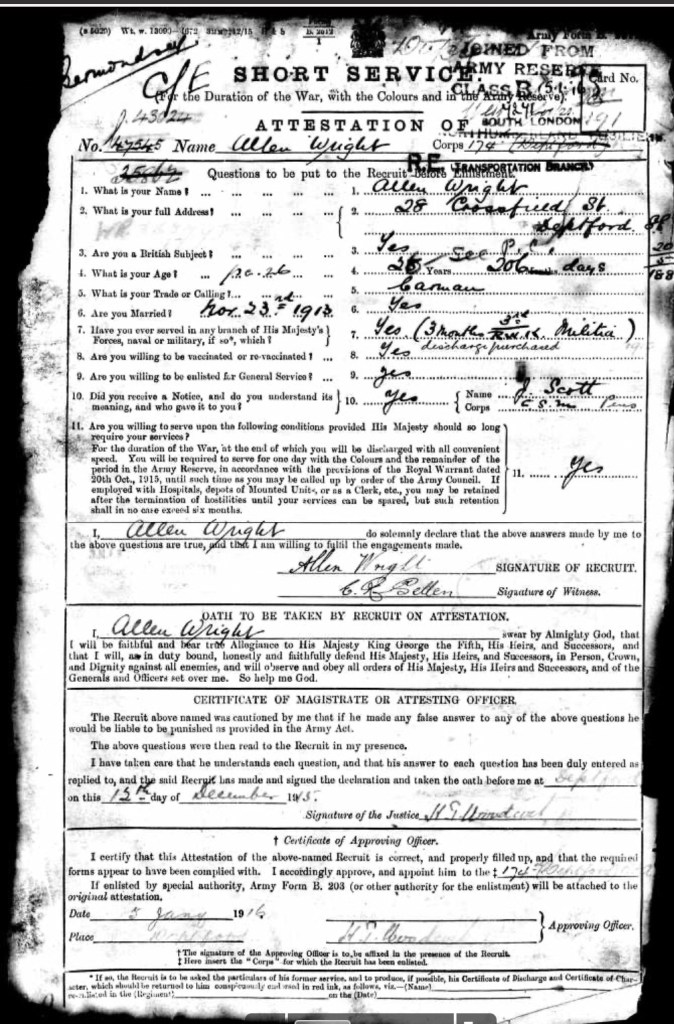

Allen Wright was my 2 x great uncle and he enlisted nine days after Britain declared war on Germany. I suspect his motivation was more financial than patriotic! He presented himself to the recruitment office at Woolwich on 13th August 1914. By this time he had changed occupations and was now a carman (delivery driver). The age on Allen’s attestation form is slightly at odds with the age on his marriage certificate and would vary slightly on future forms. His marriage certificate would make him 24 or 25 when he enlisted and previous census information supports that.

He was described as 5’2” tall, weighed 118lbs, his chest expanded from 341/2 to 361/2 inches and he had a fresh complexion, grey eyes and light brown hair. Another similar form also said he had slight flat feet, that his physical development was good and he had been vaccinated in infancy and since. He was allotted the number 128 and was sent to an infantry battalion, the 6th Royal West Kent Regiment which was formed the day after he enlisted.

Within two months he had been discharged on 8th October 1914 as “not likely to become an effective soldier” as per King’s Regulations KR 292 iii (c). This action was taken following his absence from evening roll call on three occasions. On 30th August absent until 9.45pm the following evening, forfeited two days pay. On 20th September absent until 8pm on 22nd, forfeited three days pay. On 26th September absent until 9.45pm 2nd October, when there was also a deficiency in his equipment and he forfeited seven days pay. By this time the battalion had moved to Purfleet in Essex.

Allen’s file was noted: “indifferent, frequently absent, only lasted 9 weeks.” He was discharged on the same day his brother, John William, enlisted into the Army Service Corps. Undeterred, five days later Allen followed his brother’s example and re-enlisted, into the Army Service Corps on 13th October 1914. There are few details of his time in the ASC and at first I thought it was a stray form from another Allen Wright that had been misfiled. However, the address and name of his wife overleaf are the same and the burnt, jagged corner of the paper matches up both sides. An addition to his physical description was a mole/scar, but I don’t know where because that part of the description was burnt off the paper. He lasted only 63 days until 14th December 1914 but there are no other details. Perhaps those details have been misfiled elsewhere or were completely burnt?

It appears that Allen stayed away (or maybe was rejected) from recruiting offices for another year. His third and final attestation was at Deptford on 12th December 1915, certified on 15th December and final approval on 5th January 1916 when he was mobilised and posted to 174 Brigade of the Royal Field Artillery at Woolwich. However, his re-enlistment was not the end of his misdeeds!

On 14th April 1916 he was posted as a driver, L/47545, to 6 Army Reserve – from which he promptly absented himself the next day! This is such a curious circumstance in view of his posting to a local unit and his duties were the same as his prewar occupation – a driver. Why would he do that? He was apprehended by a civil police officer on 18th April, Sergeant Bridgeman, and forfeited eight days pay. This is a pattern that repeated itself for the next two months.

On 25th April 1916 he was posted to 4 Army Reserve, went AWOL again on 30th and on his return got 7 days field punishment, before returning to duty on 11th May. It seems being shackled was the only way to keep Allen where he was supposed to be because, shortly after the punishment ended, he went absent without leave again! From 21st May to 19th June for which he got 14 days detention, forfeited 30 days pay and he was to be dispersed afterwards to an overseas unit.

There was a Court of Enquiry at Woolwich on 15th June 1916:-

“… for the purpose of investigating and recording the absence without leave from his duty and deficiency, if any, in the Arms, Ammunition, Equipment, Instruments, Regimental Necessaries or Clothing of L/47545 Driver A. Wright.”

The verdict was:-

“The court declares that no L/47545 Driver A. Wright of the Drivers’ Section 4 A Reserve Brigade RFA illegally absented himself at Woolwich on the 21st day of May 1916. He was deficient and is still so deficient of the following articles: 1 B [I can’t make out the word] cap, 1 shirt cotton, 1 braces pair, 1 boots ankle pair, 1 cap SD, 1 drawers cotton pairs, 1 jacket SD, 1 puttee pairs, 1 socks worsted pairs, 1 Great Coat value £1-11-3p, 1 spurs “jacks” value 4-8p.”

Shortly after Allen was detained he escaped from custody. He deserted at Woolwich on 22nd June 1916; on 20th July he was declared illegally absent.

As you can see from Army Form B 252 Allen was absent for 251 days.

According to another record he was “arrested on private information after 2 months enquiry” by 921B Police Constable Herbert Percy and detained at Deptford Police Station on 28th February 1917. I wonder who that person was and if (s)he collected a reward?

He was escorted to Greenwich Police Court the next day, tried at Woolwich Dockyard by District Court Martial on 13th March and convicted:-

“Desertion and losing by neglect his clothing. To undergo detention for 10 months and put under stoppages of pay. All former service forfeited on conviction of desertion.”

The mind boggles at how he could have “lost” such items as his underwear but no doubt he sold the Great Coat and perhaps some of the other clothing as well. On 27th April 1917 a telegram advised that Allen was to be transferred from detention at Woolwich to detention barracks at Aldershot for drafting overseas. Once there he found himself at Cambridge Hospital, Aldershot, presumably for a check up, on the last day of the month. He was diagnosed with a flat foot and “should have a Jones boot, heel raise 1/3” on inside and patch behind head of 1st metatarsal.”

Perhaps the subsequent fitting of the special boot gave the copycat Harry Houdini the opportunity to go on a little outing again – yes, really! There is yet another form on file headed Descriptive Return of Allen Wright who was, this time, apprehended on the 2nd July after going missing on 17th May. Yet again he was drawn back to the comforts of Deptford and was arrested, following private information, by 612R Police Constable Henry Harris and taken initially to Deptford Police Station and on to Greenwich Police Court.

On 3rd July the Commander of the detention barracks at Woolwich sent a telegram to the Officer Commanding 19 Reserve Battery Royal Field Artillery (I cannot make out the location) to say that Driver Wright should be sent to Woolwich to complete the unexpired portion of his sentence.

A further record, dated 1st August, says Allen had 165 days remitted and that he went “To Duty” i.e. the remainder of his detention was cancelled. I assume that his superiors were exasperated and wanted to get him off their hands as soon as possible. Before his departure his medical note was updated on 25th July 1917 to say he:“has done full parades and had no trouble with feet.”

Allen was in the British army base camp at Etaples on the north French coast on 29th July 1917, compulsorily transferred to 21st Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers. This transfer, as a private to an infantry unit, must either have been a wake-up call in itself, or someone had a word in his ear to tell him, in no uncertain terms, that going AWOL from now on would have much more serious consequences. In any case, one assumes the reason for Allen’s repeated absences was that in England it had been so easy to return to (presumably) his wife and other family in Deptford. It’s quite amusing to think of this man having the audacity to want army pay but did not wish to do the home based job for which he voluntarily enlisted. From the time he arrived in Etaples he appears to have given no trouble whilst overseas, well nothing that made its way to the file!

Allen’s service overseas lasted just short of a year, from 2nd August 1917 until 19th July 1918, when he returned to a home based unit after being wounded. He stayed at the Etaples camp, infamous for its rigid discipline and harsh conditions, for two weeks, after which he was transferred again. Allen joined the 16th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment on 14th August 1917 and Private Wright’s service number changed to 43024. At the time he joined the 16th West Yorks they were located in the area of the north French coalfields around Lens, which had been fiercely fought over during the Battle of Loos in September 1915. For long periods this war was played out from trench lines gained following such battles; trench lines of both sides separated by small areas of No Man’s Land. It was a war of attrition for long periods of time, men were rarely in physical combat with the enemy, however front line trenches were still dangerous places, being vulnerable to artillery firepower and snipers.

The battalion’s war diary reveals that around about the time of Allen’s arrival, they moved from a camp behind the lines (Ottawa Camp) to the transport lines at Neuville St Vaast to go up to their section of trench lines. They relieved the 11th East Lancs Regiment during the night of 16th/17th August 1917.

Below is a short quote from the battalion’s war diary around the time of Allen’s arrival which illustrates a typical stay in the trenches.

“From 17/8 to 24/8 work was carried on in the trenches cleaning up, widening, deepening, building Baby Elephant shelters and strengthening the wire defences in front of the advance line.”

I couldn’t resist that quote to give me the excuse to post the photo below of a full-grown elephant shelter! It was taken by an official photographer on the Western Front, Lieutenant Ernest Brooks, in 1916 and is part of the Imperial War Museum archive, reference IWM Q 1593.

During that tour of duty enemy trench mortars were active and 15 yards of trench was blown in leaving three men wounded and one dead. There was also a trench raid carried out on 19th August and one prisoner was taken. A Second Lieutenant was wounded by machine gun fire one night when inspecting advanced outposts.

Having experienced the exertions of moving from rest billets to trenches, and repeat, repeat, repeat … Allen and his new colleagues had an extended period away. On 1st October 1917 they went, via light railway and marching through peaceful countryside, to the back area of Bray. They stayed for two weeks, during which time they had baths, clean uniforms, they cleaned their equipment, practised on the firing range, went to lectures and demonstrations and took part in tactical exercises in the open countryside. On Sunday 7th October there was a Church of England service in the Church Army Hut and those that had watches and clocks put them back an hour, in line with Greenwich Mean Time.

They returned to a support line trench at Arleux en Gohelle. On 16th October they endured a heavy bombardment resulting in 21 other ranks wounded and one officer. Rotations began again and the weather turned, in the words of the war diary, decidedly worse. There was so much rain that sections of trench walls collapsed and in places were impassable, which kept men busy in horrible conditions trying to rectify the situation.

Allen’s file notes that he was in hospital on 1st December as a gas casualty. As far as I can tell this occurred on 12th November, so I assume the gap is due to Allen being in a casualty evacuation chain and paperwork catching up with the file. The battalion war diary notes:

“On the night of 12th/13th the enemy shelled the vicinity of battalion headquarters and the left sector with gas shells, but although the shells fell quite close to Manitoba Road the battalion only had 5 [? illegible word] cases of gas poisoning.”

There is no further record to indicate how severe his condition was or how long or where he was hospitalised. The next fact I know about Allen is that he was attached to the 3rd Entrenching Battalion at the end of February 1918. The British Army was forced into a radical reorganisation early in 1918 because of a manpower crisis. It was decided to reduce the number of infantry battalions but create 25 entrenching battalions specifically for essential manual labouring tasks, assisting tunnellers, pioneers and engineers.

The next mention of Allen in his file is for 28th March 1918 when he was posted to 1st West Yorkshire Regiment. Then in June 1918 he was hospitalised again. The 1st West Yorkshire Regiment was located in the Ypres Salient at the time, in a camp where the usual routines of training, cleaning up etc were taking place. On 21st June Allen may have been one of the 467 other ranks (and 15 officers) inspected by a party of senior officers from the upper echelons of the army. Two days later the following communication was received by the battalion:

“The Brigadier has much pleasure in conveying to all ranks of the Brigade the appreciation of the Army, Corps and Divisional Commanders on the turn out and general bearing of the men of the inspection parade yesterday. The turn out showed attention to detail and reflected credit on all concerned.”

There again, Allen could have been with the transport section who were inspected separately on 25th, by which time he was in hospital with influenza, escaping the fate of 17 of his comrades who became casualties to snipers, whilst moving from one location to another, on 27th June. The battalion war diary entry for the end of the month reveals how illness, as well as wounds, was a significant medical issue. It says that 164 men were evacuated sick during June. The reorganisation that had taken place earlier that year resulted in the loss of one out of four battalions per brigade and this meant 1st West Yorks, despite temporary hospitalisations, were not too far short of being at full strength – 40 officers and 813 other ranks.

Again, I do not know for what period Allen was away, but it wasn’t long before he was back in hospital after being wounded during the night of 14th/15th July 1918. Whenever he returned to the battalion, it was to the usual rotations in the neighbourhood of Dickebusch, south of Ypres. Perhaps he had been under canvas a month previously, in one of the tents shown in the foreground of this photo taken by 53 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps on 8th August 1918. Imperial War Museum reference Q79228D.

Although the battalion came under hostile shelling whilst in the trenches, it resulted in few casualties. That changed when their rotation in reserve was cut short by a few days and they assembled in a trench for an attack on the enemy. It was for a major trench raid rather than being part of a full scale battle and it was during this action that Allen sustained a gun shot wound which damaged his right eye. The battalion war diary entry says:-

“At 6pm the battalion attacked the enemy front [it then gives trench map references] with 2nd Durham Light Infantry on left and 2 companies of 1st Middlesex Regiment on right. [1st West Yorkshire] B and C [Companies] assaulting with D in support. Whole attack went in splendid style and by 6.45pm all objectives were reported taken. The battalion captured 3 officers and about 250 prisoners and 9 machine guns and many maps and documents etc. C Company suffered heavily going through Ridge Wood, although casualties were very slight and caused to a certain extent by men rushing into our own barrage. Enemy defensive barrage was not heavy or well placed. Enemy was seen several times during the day collecting for counter attack but was disturbed by our own infantry on each occasion.”

Allen entered the casualty clearing chain which saw him eventually admitted to 83rd General Hospital Boulogne, a specialist unit for the treatment of eye, face and jaw injuries, on 16th July 1918. Three days later he sailed on the Hospital Ship St Denis and went into one of over 200 hospitals taking war casualties in the London area. Allen was admitted to the 2nd London Hospital in St Mark’s College (formerly an educational establishment which reverted back after the war) 552 King’s Road, Chelsea. By 1917 the hospital had beds for 170 officers and 974 other ranks.

Allen next turns up on 26th August at Brighton Grove Military Hospital which, contrary to its name, was located in Newcastle upon Tyne. Therein lies a twist to the tale because it was a specialist hospital for venereal disease and Allen was being treated for gonorrhea. VD was a very common affliction amongst troops serving in France and Belgium, where there were licensed brothels. In 1916 one in five of all hospital admissions of British and dominion troops were for VD. During the war, 400,000 cases were treated, despite the warning tucked inside pay books cautioning against the temptations of wine and women!

In another twist to this story, whilst in hospital Allen requested that his wife’s separation allowance be stopped due to her misconduct. So, did he have a short period of home leave when he discovered this, or did he receive some sort of written communication? Was his condition actually caused by Mary Ann – in some cases symptoms can show within two days? Or more likely they had both been sexually active with “others”. Misconduct works both ways! In his memoirs Private Frank Richards, who served continuously on the Western Front, recorded men’s responses to the message in the pay book: “They may as well have not been issued for all the notice we took of them.”[1]

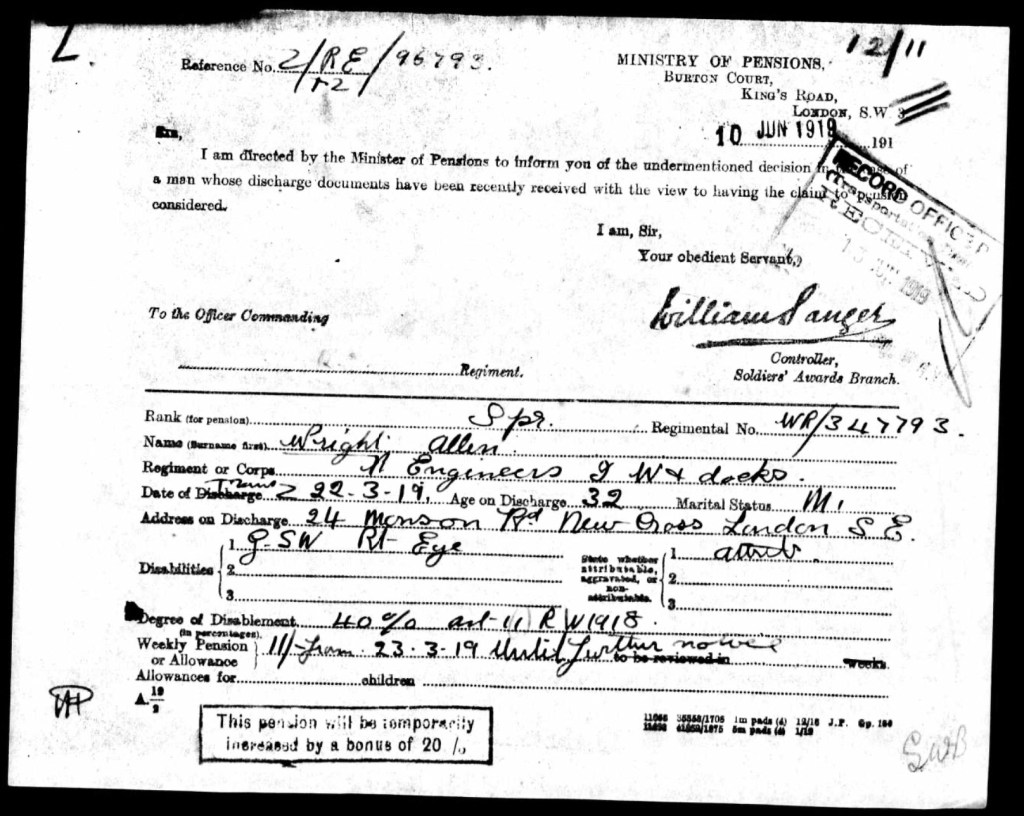

On discharge from hospital Allen went for processing to the Ripon (Yorkshire) Transfer Centre on 2nd October 1918. He was posted to the Royal Engineers as sapper 347793 at Richborough (Kent) the file records his home address as that of his mother. A statement of his disability describes defective eyesight due to shrapnel wound right eye. Right eye rupture of choroid[2], vision only in lower portion of field of vision. Left eye some hyperopia[3] eye otherwise normal and quite healthy. Glasses not advisable.

Another file note says: “permanently and compulsorily transferred under AC1 720/18 in exigencies of the service at most advantageous rates of pay” and yet, despite those advantageous rates, what did Allen do a few days later? Yep – he went AWOL!

The Regimental Conduct Sheet dated 9th October 1918:-

“Richboro’ 9/10/18 when on active service from 21.30 until apprehended by the civil police at Deptford at 04.15 on 12/10/18 (3 days) by Sgt Standhaven. Deducted 10 days pay.”

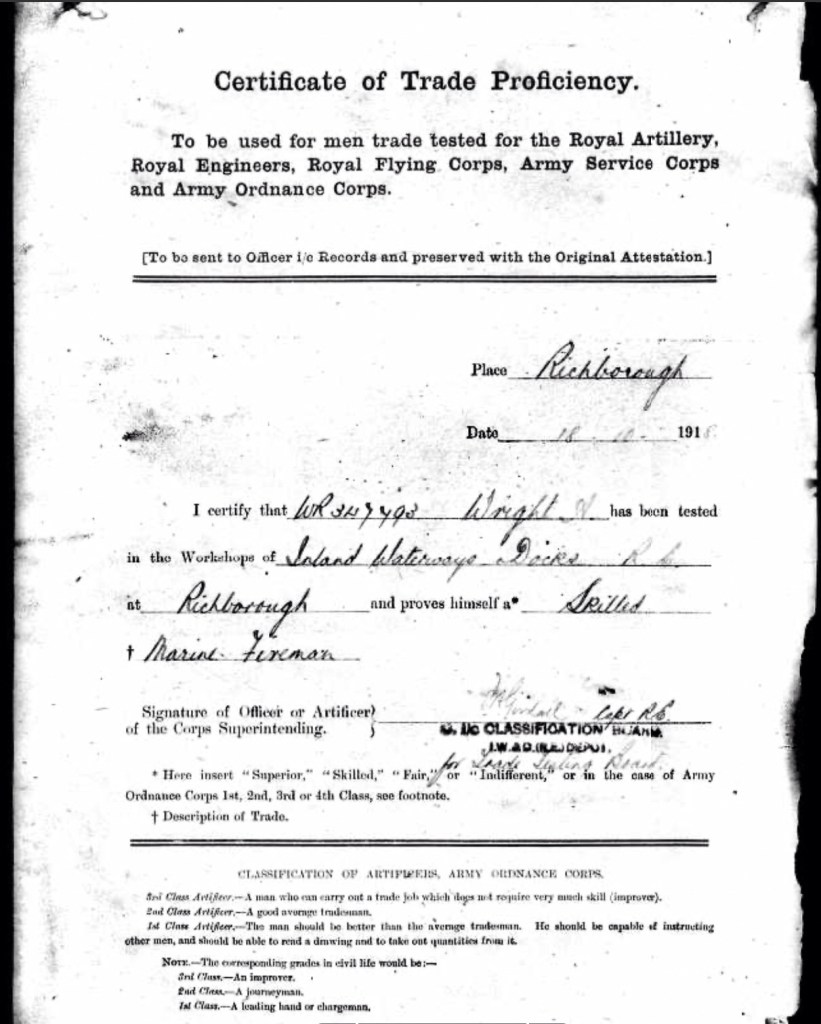

He was returned to Richborough Depot under escort, where he worked with the Royal Engineers of the Inland Waterways and Docks Board. Allen really was a conundrum! He was obviously a quick learner in other respects because, after he returned to Richborough Depot he was subsequently awarded a “skilled trade and special qualifications Marine Fireman Certificate”, on 18th October 1918.

The war’s end was now very close and Allen managed to stay out of trouble until then! However, before he was actually demobilised he over-stayed his pass for one day and 15 hours at Southampton in January 1919. On demobilisation, 23rd February, he was issued the standard Protection Certificate and Certificate of Identity and was classed as Army Reserve Z i.e. returned to civilian life but obliged to return to service if necessary. He was awarded a pension of 11/- a week as from 23rd March 1919 because of his 40% disability due to war service.

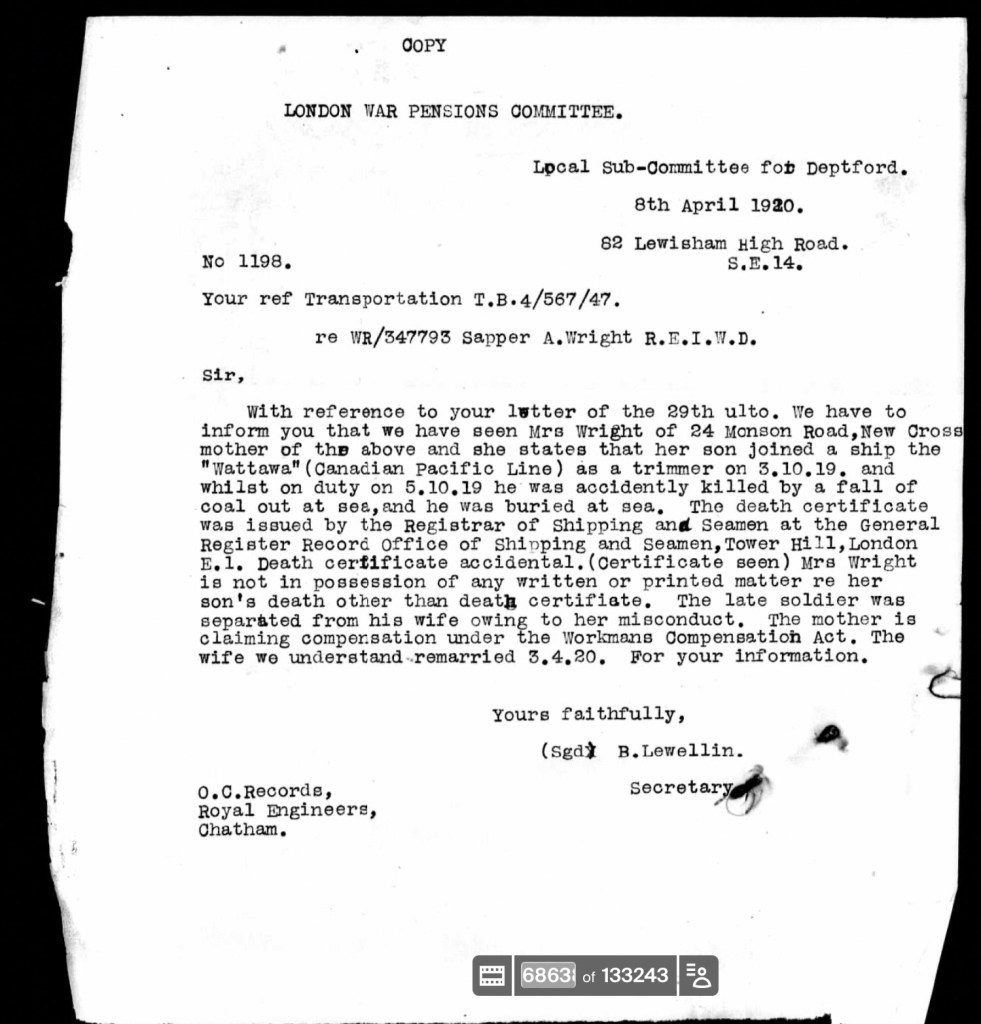

Allen then joined the Merchant Navy and went to sea as coal trimmer– and that’s when his luck ran out and his story ended. He was working as a coal trimmer on a Canadian and Pacific Line ship, SS Mattawa, when he was accidentally killed at sea on 5th October 1919 “killed by a fall of coal”. Coal trimmers did all the coal related jobs on board ship, the most important being to level the heap, by shovelling and raking, into all the recesses of the hold so that the ship would float safely. I can’t help wondering if there was some misdeed involved in the unfortunate circumstance of his death – perhaps he was skivving off asleep in the coal hold or messing around? He was buried at sea.

Allen’s mother applied for compensation but it’s not clear whether she received anything or not. By this time his wife had had a child by the man she subsequently married following Allen’s death.

There is an unsigned receipt on Allen’s file for his British War and Victory Medals. Sadly, as with other servicemen in my family that I have researched, I do not know what happened to those medals.

Also, sadly, I do not have any photographs of Allen or other relatives who served during the Great War.

[1] Richards, Frank, Old Soldiers Never Die, a memoir first published in 1933 and republished since.

[2] A thin layer of tissue that is part of the middle layer of the wall of the eye, filled with blood vessels.

[3] A condition that makes your eye look up all the time.